tecznotes

Michal Migurski's notebook, listening post, and soapbox. Subscribe to ![]() this blog.

Check out the rest of my site as well.

this blog.

Check out the rest of my site as well.

Aug 23, 2009 4:09am

geological training wheels

David Smith has an excellent post on Dunwich, Suffolk that ties together several historical and paleontological threads connected to the town and the North Sea generally.

Some excerpts of excerpts:

The town was losing ground as early as 1086 when the Domesday Book, a survey of all holdings in England, was published; between 1066 and 1086 more than half of Dunwich's taxable farmland had washed away. Major storms in 1287, 1328, 1347, and 1740 swallowed up more land. By 1844, only 237 people lived in Dunwich.

Also:

The British continental shelf contains one of the most detailed and comprehensive records of the Late Quaternary and Holocene landscapes in Europe. This landscape is unique in that it was extensively populated by humans but was rapidly inundated during the Mesolithic as a consequence of rising sea levels as a result of rapid climate change.

And:

In 10,000 BC, hunter-gatherers were living on the land in the middle of the North Sea. By 6,000 BC, Britain was an island.

This and the Bering land bridge make me think of slow movements that stretch out the bounds of possibility. Imagine living on the North Sea plain as it fills in with water over a period of four thousand years. For a few generations, you can move freely from east to west and back. Soon, rivers and marshes might start to creep in and eventually the two landmasses are separated, but still within a short row of each other.

The psychological space between the two coasts starts small; it's understood that the water boundary between is easily surmountable because it's just the equivalent of a creek or a bay. As the separation grows, the mental model of the growing North Sea continues to flag it as a path rather than a wall, you just have to improve your transportation technology periodically to continue moving back and forth. This is like learning to ride a bike with training wheels: you get used to the idea of being upright while you have a shim in place, then as the shim goes away you learn to remain upright on your own. Keep moving, balance with the handlebars. Skills that appear impossible to learn are acquired through the use of now-gone crutches.

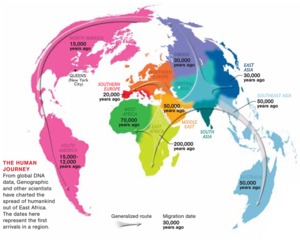

Look at this map that Matthew Hurst posted today:

You can see a 50,000 year gap between settlements on either side of the 8 mile wide Strait of Gibraltar. There's no such gap between England and the continent, those places started out settled together, and remained so even after the Holocene split. The now-submerged floor of the North Sea was like a set of prehistoric training wheels, helping to mark the path to Britain as a possibility and encouraging the upkeep of technology to keep it so. The always-divided Strait of Gibraltar did no such thing. Knowing that something is possible makes it seem sane to work to attain it. Believing that something is easy can have the same effect: "I once asked Ivan, 'How is it possible for you to have invented computer graphics, done the first object oriented software system and the first real time constraint solver all by yourself in one year?" And he said "I didn't know it was hard." Moore's law in computer development is like this as well, establishing a base rate of expectation to guide the frantic pace of development for decades afterward.

Anyway.

Comments (1)

That's... very very interesting. Culture informing the scope of possibility. I'll point out also the lack of any gap, other than water, between china and australia. We just kept going there. (See Jared Diamond's "Guns, Germs and Steel" heh)

Posted by Boris Anthony on Sunday, August 23 2009 11:42pm UTC

Sorry, no new comments on old posts.