tecznotes

Michal Migurski's notebook, listening post, and soapbox. Subscribe to ![]() this blog.

Check out the rest of my site as well.

this blog.

Check out the rest of my site as well.

Jun 9, 2017 10:31pm

blog all dog-eared pages: human transit

This week, I started at a new company. I’ve joined Remix to work on early-stage product design and development. Remix produces a planning platform for public transit, and one requirement of the extensive ongoing process is to have read Jarrett Walker’s Human Transit cover-to-cover. Walker is a longtime urban planner and transit advocate whose book establishes a foundation for making decisions about transit system design. In particular, Walker advocates time and network considerations in favor of simple spatial ones.

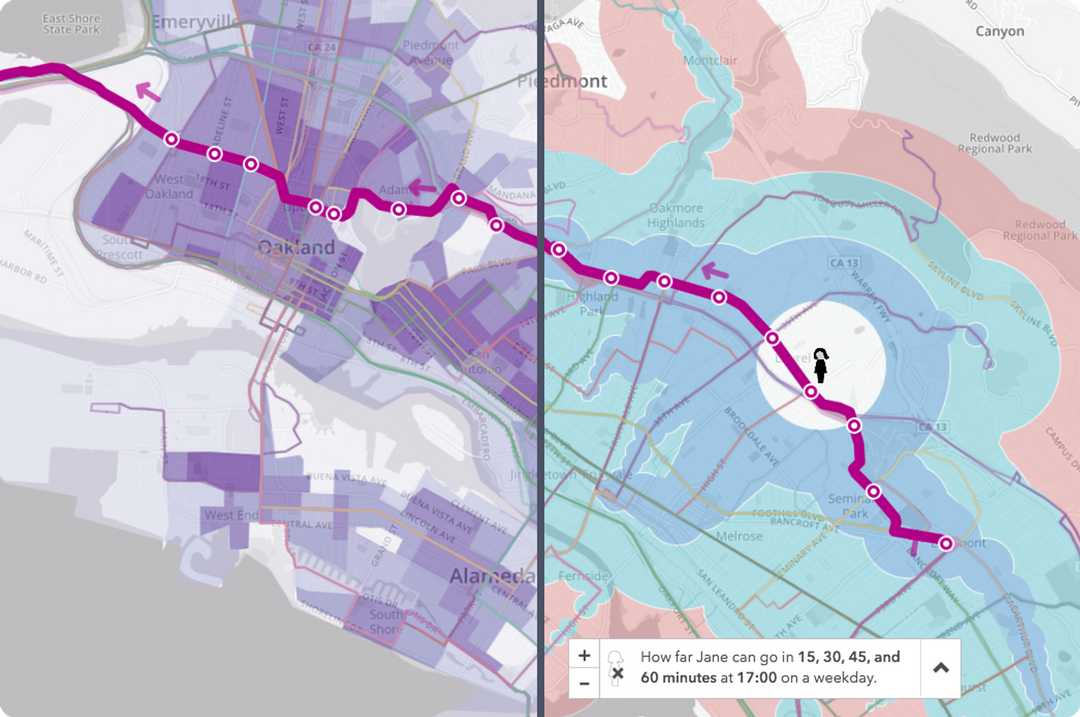

Many common public ideas about transit system design are actually misapplied from road network design when the two are actually quite different. For example, the frequency of transit vehicles (headway) has a much greater effect than their speed on the usability of a system. Uninformed trade-offs between connected systems and point-to-point systems can lead to the creation of unhelpful networks with long headways. Interactions between transit networks and the layout of streets they’re embedded in can undermine the effectiveness of transit even when it exists. All of this suggests that new visual mapmaking tools would be a critical component of better transit design that meets user needs, like the “Jane” feature of the current Remix platform showing travel times through a network taking headways into account. Here’s how far a user of public transit in Oakland can move from the Laurel Heights neighborhood on a weekday:

There’s an enormous opportunity here to apply statistical, urban, and open data to the problems of movement and city design.

These are a few of the passages from Human Transit that piqued my interest.

What even is public transit, page 13:

There are several ways to define public transit, so it is important to clarify how I’ll be using the term. Public transit consists of regularly scheduled vehicle trips, open to all paying passengers, with the capacity ti carry multiple passengers whose trips may have different origins, destinations, and purposes.

On the seven demands for a transit service, page 24:

In the hundreds of hours I’ve spent listening to people talk about their transit needs, I’ve heard seven broad expectations that potential riders have of a transit service that they would consider riding: 1) It takes me where I want to go, 2) It takes me when I want to go, 3) It is a good use of my time, 4) It is a good use of my money, 5) It respects me in the level of safety , comfort, and amenity it provides, 6) I can trust it, and 7) It gives me freedom to change my plans. … These seven demands, then, are dimensions of the mobility that transit provides. They don’t yet tell us how good we need the service to be, but they will help us identify the kinds of goodness we need to care about. In short, we can use these as a starting point for defining useful service.

On the relationship between network design and freedom, pages 31-32:

Freedom is also the biggest payoff of legibility. Only if you can remember the layout of your transit system and how to navigate it can you use transit to move spontaneously around your city. Legibility has two parts: 1) simplicity in the design of the network, so that it’s easy to explain and remember, and 2) the clarity of the presentation in all the various media.

No amount of brilliant presentation can compensate for an overly-complicated network. Anyone who has looked at a confusing tangle of routes on a system map and decided to take their car can attest to how complexity can undermine ridership. Good network planning tries to create the simplest possible network. Where complexity is unavoidable, other legibility tools help customers to see through the complexity and to find patterns of useful service that may be hidden there. For example, chapter 7 explores the idea of Frequent Network maps, which enable you to see just the lines where service is coming soon, all day. These, it turns out, are not just a navigation tool but also a land use planning tool.

On the distance between stops, pages 62-63:

Street network determines walking distance. Walking distance determines, in part, how far apart the stops can be. Stop spacing determines operating speed. So yes, the nature of the local street network affects how fast the transit line can run!

How do we decide about spacing? Consider the diamond-shaped catchment that’s made possible by a fine street grid. Ideal stop spacing is as far apart as possible for the sake of speed, but people around the line have to be able to get to it. In particular, we’re watching two areas of impact.

First, the duplicate coverage area is the area that has more than one stop within walking distance. In most situations, on flat terrain, you need to be able to walk to one stop, but not two, so duplicate coverage is a waste. Moving stops farther apart reduces the duplicate coverage area, which means that a greater number of unique people and areas are served by the stops.

Second, the coverage gap is the area that is within walking distance of the line but not of a stop. As the move stops farther apart, the coverage gap grows.

We would like to minimize both of these things, but in fact we have to choose between them. … Which is worse: creating duplicate coverage area or leaving a coverage gap? It depends on whether your transit system is designed mainly to meet the needs of transit-dependent persons or to compete for high ridership.

On Caltrain and misleading map lines, pages 79-80:

Sometimes, commuter rail is established in a corridor where the market could support efficient two-way, all-day frequent rapid transit. Once that happens, the commuter rail service can be an obstacle to any further improvement. The commuter rail creates a line on the map, so many decision makers assume that the needs are met, and may not understand that the line’s poor frequency outside the peak prevents it from functioning as rapid transit. At the same time, efforts to convert commuter rail operations to all-day high-frequency service (which requires enough automation to reduce the number of employees per train to one, if not zero) founder against institutional resistance, especially within labor unions. (Such a chance wouldn’t necessarily eliminate jobs overall, but it would turn all the jobs into train-driver jobs, running more trains)

This problem has existed for decades, for example, around the Caltrain commuter rail line between San Francisco and San Jose. This corridor has the perfect geography for all-day frequent rapid transit: super-dense San Francisco at one end, San Jose at the other, and a rail that goes right through the downtowns of almost all the suburban cities in between. In fact, the downtowns are where they are because they grew around the rail line, so the fit between the transit and urban form could not be more perfect.

…

Caltrain achieves unusually high farebox return (percentage of operating cost paid by fares) because it runs mostly when it’s busy, but its presence is also a source of confusion: the line on the map gives the appearance that this corridor has rapid transit service, but in fact Caltrain is of limited use outside the commute hour.

On cartographic emphasis and what to highlight, pages 88-89:

If a street map for a city showed every road with the same kind of line, so that a freeway looked just like a gravel road, we’d say it was a bad map. If we can’t identify the major streets and freeways, we can’t see the basic structure of the city, and without that, we can’t really make use of the map’s information. What road should a motorist use when traveling a long distance across the city? Such a map wouldn’t tell you, and without that, you couldn’t really begin.

So, a transit map that makes all lines look equal is like a road map that doesn’t show the difference between a freeway and a gravel road.

…

Emphasizing speed over frequency can make sense in contexts where everyone is expected to plan around the timetable, including peak-only commute services and very long trips with low demand. In all other contexts, though, it seems to be a common motorist’s error. Roads are there all the time, so their speed is the most important fact that distinguishes them. But transit is only there if it’s coming soon. If you have a car, you can use a road whenever you want and experience its speed. But transit has to exist when you need it (span) and it needs to be coming soon (frequency). Otherwise, waiting time will wipe out any time savings from faster service. Unless you’re comfortable planning you life around a particular scheduled trip, speed is worthless without frequency, so a transit map that screams about speed and whispers about frequency will be sowing confusion.

On the effects of delay in time, page 98:

In most urban transit, what matters is not speed by delay. Most transit technologies can go as fast as it’s safe to go in an urban setting—either on roads or on rails. What matters is mostly what can get in their way, how often they will stop, and for how long. So when we work to speed up transit, we focus on removing delays.

Delay is also the main source of problems of reliability. Reliability and average speed are different concepts, but both are undermined by the same kinds of delay, and when we reduce delay, service usually runs both faster and more reliably.

Longer-distance travel between cities is different, so analogies from those services can mislead. Airplanes, oceangoing ships, and intercity trains all spend long stretches of time at their maximum possible speed, with nothing to stop for and nothing to get in their way. Urban transit is different because a) it stops much more frequently, so top speed matters less than the stops, and b) it tends to be in situations that restrict its speed, including various kinds of congestion. Even in a rail transit system with an unobstructed path, the volume of trains going through imposes some limits, because you have to maintain a safe spacing between them even as they stop and start at stations.

On fairness, usage, and politics, page 105:

On any great urban street, every part of the current use has its fierce defenders. Local merchants will do anything to keep the on-street parking in front of their businesses. Motorists will worry (not always correctly) that losing a lane of traffic means more congestion. Removing landscaping can be controversial, especially if mature trees are involved.

To win space for transit lanes in this environment, we usually have to talk about fairness. … What if we turned a northbound traffic lane on Van Ness into a transit lane? We’re be taking 14 percent of the lane capacity of these streets to serve about 14 percent of the people who already travel in those lanes, namely, the people already using transit.

On locating transit centers at network connection points, pages 176-177:

If you want to serve a complex and diverse city with many destinations and you value frequency and simplicity, the geometry of public transit will force you to require connections. That means that for any trip from point A to point B, the quality of the experience depends on the design of not just A and B but also of a third location, point C, where the required connection occurs.

…

If you want to enjoy the riches of your city without owning a car, and you explore your mobility options through a tool like the Walkscore.com or Mapnificent.net travel time map, you’ll discover that you’ll have the best mobility if you locate at a connection point. If a business wants its employees to get to work on transit, or if a business wants to serve transit-riding customers, the best place to locate is a connection point where many services converge. All these individual decisions that generate demand for especially dense development—some kind of downtown or town center—around connection points.

…

In the midst of these debates, it’s common to hear someone ask: “Can’t we divide this big transit center into two smaller ones? Can’t we have the trains connect here and have the buses connect somewhere else, at a different station?” The answer is almost always no. At a connection point that is designed to serve a many-to-many city, people must be able to connect between any service and any other. That only happens if the services come to the same place.

On the importance of system geometry, page 181:

We’ve seen that the ease of walking to transit stops is a fact about the community and where you are in it, not a fact about the transit system. We’ve noticed that grids are an especially efficient shape for a transit network, so that’s obviously an advantage for gridded cities, like Los Angeles and Chicago, that fit that form easily. We’ve also noticed that chokepoints—like mountain passes and water barriers of many cities—offer transit a potential advantage. We’ve seen how density, both residential and commercial, is a powerful driver of transit outcomes, but that the design of the local street network matters too. High-quality and cost-effective transit implies certain geometric patterns. To the extent that those patterns work with the design of your community, you can have transit that’s both high-quality and cost-effective. To the extent that they don’t, you can’t.

On looking ahead by twenty years, page 216:

Overall, in our increasingly mobile culture, it’s hard to care about your city twenty years into the future, unless you’re one of a small minority who have made long-term investments there or you have a stable family presence that you believe will continue for generations.

But the big payoffs rest in strategic thinking, and that means looking forward over a span of time. I suggest twenty years as a time frame because almost everybody will relocate in that time, and most of the development not contemplated in your city will be complete. That means virtually every resident and business will have a chance to reconsider its location in light of the transit system planed for the future. It also means that it’s easier to get citizens thinking about what they want the city to be like, rather than just fearing change that might happen to the street where they live now. I’ve found that once this process gets going, people enjoy talking thinking about their city twenty years ahead, even if they aren’t sure they’ll live there then.

Jun 6, 2016 11:37pm

blog all dog-eared pages: the best and the brightest

David Halberstam’s 1972 evisceration of the Vietnam War planning process during Kennedy and Johnson’s administrations has been on my list to read for a while, for two reasons. Being born just after the war means that I’ve heard for my whole life about what a mistake it was, but never understood the pre-war support for such a debacle. Also, I’m interested in the organizational problems that might have led to the entanglement in a country fighting for its independence from foreign occupations over centuries. How did anyone think this was a good idea? According to Halberstam, the U.S. government had limited its own critical capacity due to McCarthyist purges after China’s revolution, and Johnson in particular was invested in Vietnam being a small, non-war. In the same way that clipping lines of communication can destroy a conspiracy’s ability to think, the system did not really “think” about this at all. Many similarities to Iraq 40 years later.

The inherent unattractiveness of doubt is an early theme; the people who might have helped Kennedy and later Johnson make a smarter move by preventing rash action did not push to be a part of these decisions. Sometimes it’s smartest to make no move at all, but the go-getters who go get into positions of power carry a natural bias towards action in all situations. Advice from doubters should be sought out. I’m grateful for the past years of Obama’s presidency who characterized his foreign policy doctrine as “Don’t do stupid shit.”

The locus of control is another theme. Halberstam shows how the civilian leadership thought it had the military under control, and the military leadership thought it had the Vietnam campaign under control. In reality, the civilians ceded the initiative to the generals, and the generals never clearly saw how the Northern Vietnamese controlled the pace of the war. Using the jungle trails between the North and South and holding the demographic advantage and a strategy with a clear goal, the government in Hanoi decided the pace of the war by choosing to send or not send troops into the south. America was permanently stuck outside the feedback loop.

I would be curious to know if a similar account of the same war is available from the Northern perspective; were the advantages always obvious from the inside? How is this story told from the victor’s point of view?

Here are some passages I liked particularly.

On David Reisman and being a doubter in 1961, page 42:

“You all think you can manage limited wars and that you’re dealing with an elite society which is just waiting for your leadership. It’s not that way at all,” he said. “It’s not an Eastern elite society run for Harvard and the Council on Foreign Relations.”

It was only natural that the intellectuals who questioned the necessity of America purpose did not rush from Cambridge and New Haven to inflict their doubts about American power and goals upon the nation’s policies. So people like Reisman, classic intellectuals, stayed where they were while the new breed of thinkers-doers, half of academe, half the nation’s think tanks and of policy planning, would make the trip, not doubting for a moment the validity of their right to serve, the quality of their experience. They were men who reflect the post-Munich, post-McCarthy pragmatism of the age. One had to stop totalitarianism, and since the only thing the totalitarians understood was force, one had to be willing to use force. They justified each decision to use power by their own conviction that the Communists were worse, which justified our dirty tricks, our toughness.

On setting expections and General Shoup’s use of maps to convey the impossibility of invading Cuba in 1961, page 66:

When talk about invading Cuba was becoming fashionable, General Shoup did a remarkable display with maps. First he took an overlay of Cuba and placed it over the map of the United States. To everybody’s surprise, Cuba was not a small island along the lines of, say, Long Island at best. It was about 800 miles long and seemed to stretch from New York to Chicago. Then he took another overlay, with a red dot, and placed it over the map of Cuba. “What’s that?” someone asked him. “That, gentlemen, represent the size of the island of Tarawa,” said Shoup, who had won a Medal of Honor there, “and it took us three days and eighteen thousand Marines to take it.”

On being perceived as a dynamic badass in government, relative to the First Asian crisis in Laos, 1961-63, page 88:

It was the classic crisis, the kind that the policy makers of the Kennedy era enjoyed, taking an event and making it greater by their determination to handle it, the attention focused on the White House. During the next two months, officials were photographed briskly walking (almost trotting) as they came and went with their attaché cases, giving their No comment’s, the blending of drama and power, everything made a little bigger and more important by their very touching it. Power and excitement come to Washington. There were intense conferences, great tensions, chances for grace under pressure. Being in on the action. At the first meeting, McNamara forcefully advocated arming half a dozen AT6s (obsolete World War Ⅱ fighter planes) with 100-lb. bombs, and letting them go after the bad Laotians. It was a strong advocacy; the other side had no air power. This we would certainly win; technology and power could do it all. (“When a newcomer enters the field [of foreign policy],” Chester Bowles wrote in a note to himself at the time, “and finds himself confronted by the nuances of international questions he becomes an easy target for the military-CIA-paramilitary-type answers which can be added, subtracted, multiplied or divided…”)

On questioning evidence for the domino theory, page 122:

Later, as their policies floundered in Vietnam, … the real problem was the failure to reexamine the assumptions of the era, particularly in Southeast Asia. There was no real attempt, when the new Administration came in, to analyze Ho Chi Minh’s position in terms of the Vietnamese people and in terms of the larger Communist world, to establish what Diem represented, to determine whether the domino theory was in fact valid. Each time the question of the domino theory was sent to intelligence experts for evaluation, the would back answers which reflected their doubts about its validity, but the highest level of government left the domino theory alone. It was as if, by questioning it, they might have revealed its emptiness, and would then have been forced to act on their new discovery.

On the ridiculousness of the Special Forces, page 123:

All of this helped send the Kennedy Administration into dizzying heights of antiguerilla activity and discussion; instead of looking behind them, the Kennedy people were looking ahead, ready for a new and more subtle kind of conflict. The other side, Rostow’s scavengers of revolution, would soon be met by the new American breed, a romantic group indeed, the U.S. Army Special Forces. They were all uncommon men, extraordinary physical specimens and intellectuals Ph.D.s swinging from trees, speaking Russian and Chinese, eating snake meat and other fauna at night, springing counterambushes on unwary Asian ambushers who had read Mao and Giap, but not Hilsman and Rostow. It was all going to be very exciting, and even better, great gains would be made at little cost.

In October 1961 the entire White House press corps was transported to Fort Bragg to watch a special demonstration put on by Kennedy’s favored Special Forces, and it turned into a real whiz-bang day. There were ambushes, counterambushes and demonstrations in snake-meat eating, all topped off by a Buck Rogers show: a soldier with a rocket on his back who flew over water to land on the other side. It was quite a show, and it was only as they were leaving Fort Bragg that Francis Lara, the Agence France-Presse correspondent who had covered the Indochina War, sidle over to his friend Tom Wicker of the New York Times. “Al; of this looks very impressive, doesn’t it?” he said. Wicker allowed as how it did. “Funny,” Lara said, “none of it worked for us when we tried it in 1951.”

On consensual hallucinations, shared reality, and some alarming parallels to Bruno Latour’s translation model, page 148:

In 1954, right after Geneva, no one really believed there was such a thing as South Vietnam. … Like water turning into ice, the illusion crystallized and became a reality, not because that which existed in South Vietnam was real, but because it became powerful in men’s minds. Thus, what had never truly existed and was so terribly frail became firm, hard. A real country with a real constitution. An army dressed in fine, tight-fitting uniforms, and officers with lots of medals. A supreme court. A courageous president. Articles were written. “The tough miracle man of Vietnam,” Life called [Diem]. “The bright spot in Asia,” the Saturday Evening Post said.

On the difficulty of containing military plans and the general way it’s hard to get technical and operations groups to relinquish control once granted, page 178:

The Kennedy commitment had changed things in other ways as well. While the President had the illusion that he had held off the military, the reality was that he had let them in. … Once activated, even in a small way at first, they would soon dominate the play. Their particular power with the Hill and with hawkish journalists, their stronger hold on patriotic-machismo arguments (in decision making the proposed the manhood positions, their opponents the softer, or sissy, positions), their particular certitude, made them far more powerful players than men raising doubts. The illusion would always be of civilian control; the reality would be of a relentlessly growing military domination of policy, intelligence, aims, objectives and means, with the civilians, the very ones who thought they could control the military, conceding step by step, without even knowing they were losing.

On being stuck in a trap of our own making by 1964, page 304:

They were rational men, that above all; they were not ideologues. Ideologues are predictable and they were not, so the idea that those intelligent, rational, cultured, civilized men had been caught in a terrible trap by 1964 and that they spent an entire year letting the trap grow tighter was unacceptable; they would have been the first to deny it. If someone in those days had called them aside and suggested that they, all good rational men, were tied to a policy of deep irrationality, layer and layer of clear rationality based upon several great false assumptions and buttressed by a deeply dishonest reporting system which created a totally false data bank, they would have lashed out sharply that they did indeed know where they were going.

On the timing of Robert Johnson’s 1964 study on bombing effectiveness (“we would face the problem of finding a graceful way out of the action”), page 358:

Similarly, the massive and significant study was pushed aside because it had come out at the wrong time. A study has to be published at the right moment, when people are debating an issue and about to make a decision; then and only then will they read a major paper, otherwise they are too pressed for time. Therefore, when the long-delayed decisions on the bombing were made a year later, the principals did not go back to the Bob Johnson paper, because new things had happened, one did not go back to an old paper.

Finally and perhaps most important, there was no one to fight for it, to force it into the play, to make the other principals come to terms with it. Rostow himself could not have disagreed more with the paper; it challenged every one of his main theses, his almost singular and simplistic belief in bombing and what it could accomplish.

On George Ball’s 1964 case for the doves and commitment to false hope, page 496:

Bothered by the direction of the war, and by the attitudes he found around him in the post-Tonkin fall of 1964, and knowing that terrible decisions were coming up, Ball began to turn his attention to the subject of Vietnam. He knew where the dissenters were at State, and he began to put together his own network, people with expertise on Indochina and Asia who had been part of the apparatus Harriman had built, men like Alan Whiting, a China watcher at INR; these were men whose own work was being rejected or simply ignored by their superiors. Above all, Ball was trusting his own instincts on Indochina. The fact that the others were all headed the other way did not bother him; he was not that much in awe of them, anyway.

Since Ball had not been in on any of the earlier decision making, he was in no way committed to any false hopes and self-justification; in addition, since he had not really taken part in the turnaround against Diem, he was in no way tainted in Johnson’s eyes.

On slippery slopes for “our boys,” page 538:

Slipping in the first troops was an adjustment, an asterisk really, to a decision they had made principally to avoid sending troops, but of course there had to be protection for the airplanes, which no one had talked about at any length during the bombing discussion, that if you bombed you needed airfields, and if you had airfields you needed troops to protect the airfields, and the ARVN wasn’t good enough. Nor had anyone pointed out that troops beget troops: that a regiment is very small, a regiment cannot protect itself. Even as they were bombing they were preparing for the arrival of our boys, which of course would mean more boys to protect our boys. The rationale would provide its own rhythm of escalation, and its growth would make William Westmoreland almost overnight a major player, if not the major player. This rationale weighed so heavily on the minds of the principals that three years later, in 1968, when the new thrust of part of the bureaucracy was to end or limit the bombing and when Lyndon Johnson was willing to remove himself from running again, he was nevertheless transfixes by the idea of protecting our boys.

On Robert McNamara making shit up, page 581:

Soon they would lose control, he said; soon we would be sending 200,000 to 250,000 men there. Then they would tear into him, McNamara the leader: It’s dirty pool; for Christ’s sake, George, we’re not talking about anything like that, no one’s talking about that many people, we’re talking about a dozen, maybe a few more maneuver battalions.

Poor George had no counterfigures; he would talk in vague doubts, lacking these figures, and leave the meetings occasionally depressed and annoyed. Why did McNamara have such good figures? Why did McNamara have such good staff work and Ball such poor staff work? The next day Ball would angrily dispatch his staff to come up with the figures, to find out how McNamara had gotten them, and the staff would burrow away and occasionally find that one of the reasons that Ball did not have the comparable figures was that they did not always exist. McNamara had invented them, he dissembled even within the bureaucracy, though, of course, always for a good cause. It was part of his sense of service. He believed in what he did, and this the morality of it was assured, and everything else fell into place.

On the political need to keep decisions soft and vague, page 593:

If there were no decisions which were crystallized and hard, then they could not leak, and if they could not leak, then the opposition could not point to them. Which was why he was not about to call up the reserves, because the use of the reserves would blow it all. It would be self-evident that we were really going to war, and that we would in fact have to pay a price. Which went against all Administration planning; this would be a war without a price, a silent, politically invisible war.

On asking for poor service, page 595:

Six years later McGeorge Bundy, whose job it was to ask questions for a President who could not always ask the right questions himself, would go before the Council on Foreign Relations and make a startling admission about the mission and the lack of precise objectives. The Administration, Bundy recounted, did not tell the military what to do and how to do itl there was in his words a “premium put on imprecision,” and the political and military leaders did not speak candidly to each other. In fact, if the military and political leaders had been totally candid with each other in 1965 about the length and cost of the war instead of coming to a consensus, as Johnson wanted, there would have been vast and perhaps unbridgeable differences, Bundy said. It was a startling admission, because it was specifically Bundy’s job to make sure that differences like these did not exist. They existed, of course, not because they could not be uncovered but because it was a deliberate policy not to surface with real figures and real estimates which might show that they were headed toward a real war. The men around Johnson served him poorly, but they served him poorly because he wanted them to.

Dec 29, 2011 8:07am

blog all kindle-clipped locations: normal accidents

I’m reading Charles Perrow’s book Normal Accidents (Living with High-Risk Technologies). It’s about nuclear accidents, among other things, and the ways in which systemic complexity inevitably leads to expected or normal failure modes. I think John Allspaw may have recommended it to me with the words “failure porn”.

I’m only partway through. For a book on engineering and safety it’s completely fascinating, notably for the way it shows how unintuitively-linked circumstances and safety features can interact to introduce new risk. The descriptions of accidents are riveting, not least because many come from Nuclear Safety magazine and are written in a breezy tone belying subsurface potential for total calamity. I’m not sure why this is interesting to me at this point in time, but as we think about data flows in cities and governments I sense a similar species of flighty optimism underlying arguments for Smart Cities.

Loc. 94-97, a definition of what “normal” means in the context of this book:

If interactive complexity and tight coupling—system characteristics—inevitably will produce an accident, I believe we are justified in calling it a normal accident, or a system accident. The odd term normal accident is meant to signal that, given the system characteristics, multiple and unexpected interactions of failures are inevitable. This is an expression of an integral characteristic of the system, not a statement of frequency. It is normal for us to die, but we only do it once.

Loc. 956-60, defining the term “accident” and its relation to four levels of affect (operators, employees, bystanders, the general public):

With this scheme we reserve the term accident for serious matters, that is, those affecting the third or fourth levels; we use the term incident for disruptions at the first or second level. The transition between incidents and accidents is the nexus where most of the engineered safety features come into play—the redundant components that may be activated; the emergency shut-offs; the emergency suppressors, such as core spray; or emergency supplies, such as emergency feedwater pumps. The scheme has its ambiguities, since one could argue interminably over the dividing line between part, unit, and subsystem, but it is flexible and adequate for our purposes.

Loc. 184-88, on the ways in which safety measures themselves increase complexity or juice the risks of dangerous actions:

It is particularly important to evaluate technological fixes in the systems that we cannot or will not do without. Fixes, including safety devices, sometimes create new accidents, and quite often merely allow those in charge to run the system faster, or in worse weather, or with bigger explosives. Some technological fixes are error-reducing—the jet engine is simpler and safer than the piston engine; fathometers are better than lead lines; three engines are better than two on an airplane; computers are more reliable than pneumatic controls. But other technological fixes are excuses for poor organization or an attempt to compensate for poor system design. The attention of authorities in some of these systems, unfortunately, is hard to get when safety is involved.

Loc. 776-90, a harrowing description of cleanup efforts after the October 1966 Fermi meltdown:

Almost a year from the accident, they were able to lower a periscope 40 feet down to the bottom of the core, where there was a conical flow guide—a safety device similar to a huge inverted icecream cone that was meant to widely distribute any uranium that might inconceivably melt and drop to the bottom of the vessel. Here they spied a crumpled bit of metal, for all the world looking like a crushed beer can, which could have blocked the flow of sodium coolant.

It wasn’t a beer can, but the operators could not see clearly enough to identify it. The periscope had fifteen optical relay lenses, would cloud up and take a day to clean, was very hard to maneuver, and had to be operated from specially-built, locked-air chambers to avoid radiation. To turn the metal over to examine it required the use of another complex, snake-like tool operated 35 feet from the base of the reactor. The operators managed to get a grip on the metal, and after an hour and a half it was removed.

The crumpled bit of metal turned out to be one of five triangular pieces of zirconium that had been installed as a safety device at the insistence of the Advisory Reactor Safety Committee, a prestigious group of nuclear experts who advise the NRC. It wasn’t even on the blueprints. The flow of sodium coolant had ripped it loose. Moving about, it soon took a position that blocked the flow of coolant, causing the melting of the fuel bundles.

During this time, and for many months afterwards, the reactor had to be constantly bathed in argon gas or nitrogen to make sure that the extremely volatile sodium coolant did not come into contact with any air or water; if it did, it would explode and could rupture the core. It was constantly monitored with Geiger counters by health physicists. Even loud noises had to be avoided. Though the reactor was subcritical, there was still a chance of a reactivity accident. Slowly the fuel assemblies were removed and cut into three pieces so they could be shipped out of the plant for burial. But first they had to be cooled off for months in spent-fuel pools—huge swimming pools of water, where the rods of uranium could not be placed too close to each other. Then they were placed in cylinders 9 feet in diameter weighing 18 tons each. These were designed to withstand a 30-foot fall and a 30-minute fire, so dangerous is the spent fuel. Leakage from the casks could kill children a half a mile away.

That’s completely insane.

Jun 17, 2010 7:02am

blog all kindle-clipped locations: the big short

I picked up Michael Lewis's new book, The Big Short, pretty much as soon as it hit the Kindle a few weeks ago. It's a post-catastrophe account of the subprime mortgage crisis, told through the eyes of a small group of traders who shorted the supposedly unshortable mortgage backed securities that made everyone rich five years ago.

It's partially a financial story, but to me it's also a story about assumptions. I've been thinking a bit about the effects of unspoken, day-to-day dependencies that we all rely on in our lives. Can we live without them? Are we light enough on our feet to adjust when they shift? Do we even know what they are, and can we explain how they fit together? In a small company like mine, these questions can lead to some fairly serious existential crises. A few years ago, our client base seemed disproportionately tied to the galloping Web 2.0 economy. More recently, the brash announcement by Apple that Flash would be unsupported on the iPad confirmed a long-held suspicion that the platform was on rocky ground. In the trenches of my day-to-day as technology director, I've become excessively sensitive to the problems of cross-dependencies among projects, code bases, and servers. This is not so much an issue of identifying single points of failure as it is a matter of understanding which doorknobs you've tied your teeth to and subsequently forgotten.

Three questions:

- Do you depend on anything outside your control? What is it?

- Can you repeat past successes with those same externalities?

- Could you quarantine, isolate, or replace them, if you had to?

The Big Short is the story of one particular set of external dependencies that turned out to be hopelessly intertwined. Specifically, it's about the revelation that an entire class of financial products based on the performance of mortgage payments was more deeply interdependent and market-distorting than anyone had imagined. It's the moment near the end of a Stephen King novel where all the townspeople are revealed to have first names that start with "K" and they're sitting silently in their cars waiting for you up the road. NPR's Planet Money does a better job of explaining the details ("we bought the toxic asset..."), but the underpinning of the story shows how difficult it is to reject a lie when your livelihood depends on believing it.

Anyway.

Loc. 476-82, an opening anecdote showing the matter-of-fact cultural role of Wall Street greed:

When a Wall Street firm helped him to get into a trade that seemed perfect in every way, he asked the salesman, "I appreciate this, but I just want to know one thing: How are you going to fuck me?" Heh-heh-heh, c'mon, we'd never do that, the trader started to say, but Danny, though perfectly polite, was insistent. We both know that unadulterated good things like this trade don't just happen between little hedge funds and big Wall Street firms. I'll do it, but only after you explain to me how you are going to fuck me. And the salesman explained how he was going to fuck him. And Danny did the trade.

Loc. 483-87, Steven Eisman is one of the main characters, a brusque gadfly with odd listening habits:

Working for Eisman, you never felt you were working for Eisman. He'd teach you but he wouldn't supervise you. Eisman also put a fine point on the absurdity they saw everywhere around them. "Steve's fun to take to any Wall Street meeting," said Vinny. "Because he'll say 'explain that to me' thirty different times. Or 'could you explain that more, in English?' Because once you do that, there's a few things you learn. For a start, you figure out if they even know what they're talking about. And a lot of times they don't!"

Loc. 985-89, on the undesireability of defending an idea:

Inadvertently, he'd opened up a debate with his own investors, which he counted among his least favorite activities. "I hated discussing ideas with investors," he said, "because I then become a Defender of the Idea, and that influences your thought process." Once you became an idea's defender you had a harder time changing your mind about it. He had no choice: Among the people who gave him money there was pretty obviously a built-in skepticism of so-called macro thinking.

Loc. 1788-96, on the role of research that seemingly no one else wants to do. This is actually one of the most interesting aspects of The Big Short for me, the relative rarity of legwork compared to the ease of sticking to first appearances:

It wasn't a question two thirty-something would-be professional investors in Berkeley, California, with $110,000 in a Schwab account should feel it was their business to answer. But they did. They went hunting for people who had gone to college with Capital One's CEO, Richard Fairbank, and collected character references. Jamie paged through the Capital One 10-K filing in search of someone inside the company he might plausibly ask to meet. "If we had asked to meet with the CEO, we wouldn't have gotten to see him," explained Charlie. Finally they came upon a lower-ranking guy named Peter Schnall, who happened to be the vice-president in charge of the subprime portfolio. "I got the impression they were like, 'Who calls and asks for Peter Schnall?'" said Charlie. "Because when we asked to talk to him they were like, 'Why not?'" They introduced themselves gravely as Cornwall Capital Management but refrained from mentioning what, exactly, Cornwall Capital Management was. "It's funny," says Jamie. "People don't feel comfortable asking how much money you have, and so you don't have to tell them."

Loc. 1830-34, on arguing convincingly:

Both had trouble generating conviction of their own but no trouble at all reacting to what they viewed as the false conviction of others. Each time they came upon a tantalizing long shot, one of them set to work on making the case for it, in an elaborate presentation, complete with PowerPoint slides. They didn't actually have anyone to whom they might give a presentation. They created them only to hear how plausible they sounded when pitched to each other. They entered markets only because they thought something dramatic might be about to happen in them, on which they could make a small bet with long odds that might pay off in a big way.

Loc. 2206-11, more on Eisman's listening habits:

Eisman had a curious way of listening; he didn't so much listen to what you were saying as subcontract to some remote region of his brain the task of deciding whether whatever you were saying was worth listening to, while his mind went off to play on its own. As a result, he never actually heard what you said to him the first time you said it. If his mental subcontractor detected a level of interest in what you had just said, it radioed a signal to the mother ship, which then wheeled around with the most intense focus. "Say that again," he'd say. And you would! Because now Eisman was so obviously listening to you, and, as he listened so selectively, you felt flattered.

Loc. 3260-64, on $1.2 billion:

In early July, Morgan Stanley received its first wake-up call. It came from Greg Lippmann and his bosses at Deutsche Bank, who, in a conference call, told Howie Hubler and his bosses that the $4 billion in credit default swaps Hubler had sold Deutsche Bank's CDO desk six months earlier had moved in Deutsche Bank's favor. Could Morgan Stanley please wire $1.2 billion to Deutsche Bank by the end of the day? Or, as Lippmann actually put it - according to someone who heard the exchange - Dude, you owe us one point two billion.

Loc. 3413-22, on eight days of chlorine for all of Chicago:

His wife's extended English family of course wondered where he had been, and he tried to explain. He thought what was happening was critically important. The banking system was insolvent, he assumed, and that implied some grave upheaval. When banking stops, credit stops, and when credit stops, trade stops, and when trade stops - well, the city of Chicago had only eight days of chlorine on hand for its water supply. Hospitals ran out of medicine. The entire modern world was premised on the ability to buy now and pay later. "I'd come home at midnight and try to talk to my brother-in-law about our children's future," said Ben. "I asked everyone in the house to make sure their accounts at HSBC were insured. I told them to keep some cash on hand, as we might face some disruptions. But it was hard to explain." How do you explain to an innocent citizen of the free world the importance of a credit default swap on a double-A tranche of a subprime-backed collateralized debt obligation? He tried, but his English in-laws just looked at him strangely. They understood that someone else had just lost a great deal of money and Ben had just made a great deal of money, but never got much past that. "I can't really talk to them about it," he says. "They're English."

Loc. 3747-52, on being dumb and looking for grownups:

The big Wall Street firms, seemingly so shrewd and self-interested, had somehow become the dumb money. The people who ran them did not understand their own businesses, and their regulators obviously knew even less. Charlie and Jamie had always sort of assumed that there was some grown-up in charge of the financial system whom they had never met; now, they saw there was not. "We were never inside the belly of the beast," said Charlie. "We saw the bodies being carried out. But we were never inside." A Bloomberg News headline that caught Jamie's eye, and stuck in his mind: "Senate Majority Leader on Crisis: No One Knows What to Do."

Loc. 3880-82, a last word on dependencies:

The changes were camouflage. They helped to distract outsiders from the truly profane event: the growing misalignment of interests between the people who trafficked in financial risk and the wider culture. The surface rippled, but down below, in the depths, the bonus pool remained undisturbed.

Jan 16, 2009 9:05am

blog all dog-eared pages: the process of government

Arthur F. Bentley's 1908 The Process Of Government (A Study Of Social Pressures) found me through a a review in the New Yorker a few months ago. This summary got me interested:

The Process of Government is a hedgehog of a book. Its point - relentlessly hammered home - can be stated quite simply: All politics and all government are the result of the activities of groups. Any other attempt to explain politics and government is doomed to failure. It was, in his day as in ours, a wildly contrarian position. Bentley was writing The Process of Government at the height of the Progressive Era, when educated, prosperous, high-minded people believed overwhelmingly in "reform" and "good government," and took interest groups to be the enemy of these goals.

Normally I summarize the books I read, but in this case Nicholas Lemann's review is a much better and more interesting writeup than I can offer. Instead I'll just mention that it's a delivery mechanism for the kind of worldview that burrows its way into your subconscious and won't let go. I have a weakness for reductive explanations, and Bentley offers a big one: "ideas", "the public", "zeitgeist", and other hive-mind explanations of political activity are meaningless in the face of often-temporarily organized interests arrayed in groups of people, playing a species-wide game of king of the hill. Law and morality exist because they are useful and helpful to someone, somewhere, more than they are harmful. When these things fall out of kilter, organizations form to rebalance them.

Read the review, check out the passages below, and then try to celebrate Tuesday's inauguration, read a political blog, watch Milk, follow Tim O'Reilly's losing battle to define "web 2.0", bemoan the passage of Prop. 8, or digg (something) for (some reason) without seeing groups, groups, groups, and groups all vying for your attention and support.

Page 13, on reform, opportunity, the absence of personal change:

What was to be seen, in actual human life, was a mass of men making of their opportunities. The insurance presidents and trustees saw opportunities and used them. Their enemies in the fit time saw opportunities and used them. The "public" by and by awoke to what it had suffered, saw its opportunities for revenge and for future safeguard and used them. All these things happened, all of them had causes, but those causes cannot be found in a waxing and waning and change or transformation of the psychic qualities of the actors.

Page 58, Rudolf von Jhering on the usefulness of law:

He set himself in opposition on the one hand to theories which made laws take their origin in any kind of absolute will power, and on the other hand to theories which placed the origin in mere might. It was the usefulness of the law, he said, that counted.

Stripped of terminology and disputation, this came to saying that you cannot get law out of simple head work, and you cannot get it out of mere preponderance of force; law must always be good for something to the society which has it, and that quality of being good for something is the very essence of it.

The formal element of the law he placed, at this time, in the legal protection by right of action ("Klage", "Rechtsschutz"); the substantial element in "Nutzen", "Vortheil", "Gewinn", "Sicherheit des Genusses". He defined laws as legally protected interests, and said that they served "den Interessen, Bed�rfnissen, Zwecken des Verlkhes". The "subject" of the law, using the term habitual among the jurists, is the person or organization to whom its benefits pass. The protection of the law exists to assure this benefit reaching the right place.

Page 113, on beef, alternatives, and inevitability:

To take an illustration of a kind most unfavorable for my contention: Does anyone believe that a states'-rights Bryan in the president's chair could have taken any other course in dealing with the nation-wide beef industry when the time for its control had arrived than was taken by a republican? ... But given the national scope of the industry and its customers, given also its foreign trade, given the emergency for its control which was bound to come through its own growth and methods, if not in one year then in another, given presidential representation of the mass of the people on approximately the same level, could a states'-right president have found a different solution from any other president? The answer is most decidedly, No.

Page 169, on the social rootedness of emotion:

No matter how generalized or how specific the ideas and feeling are which we are considering, they never lose their reference to a "social something". The angry man is never angry save in certain situations; the highest ideal of liberty has to do with man among men. The words anger and liberty can easily be set over as subjects against groups of words in the predicate which define them. But neither anger, nor liberty, nor any feeling or idea in between can be got hold of anywhere except in phases of social situations. They stand out as phases, moreover, only with reference to certain position in the social situation or complex of situations in the widest sense, within which they themselves exist.

Page 181, on what material to study if not ideas:

When our popular leader - to revert to the Standard Oil illustration - gets upon the platform and tells us we must all rally with him to exterminate the trusts, we have so much raw material for investigation which we must take as so much activity for just what it is. If we start out with a theory about ideas and their place in politics, we are deserting our raw material even before we take a good peep at it. We are substituting something else which may or may no be useful, but which will certainly color our entire further progress, if progress we can make at all on scientific lines.

Page 197, on social activity as the raw material:

We shall find as go on that even in the most deliberative acts of heads of governments, what is done can be fully stated in terms of the social activity that passes through, or is reflected, or represented, or mediated in those high officials, much more fully than by their alleged mental states as such. Mark Twain tells of a question he put to General Grant: "With whom originated the idea of the march to the sea? Was it Grant's or was it Sherman's idea?" and of Grant's reply: "Neither of us originated the idea of Sherman's march to the sea. The enemy did it;" an answer which points solidly to the social context, always in individuals, but never to be stated adequately in terms of individuals.

Page 206, on acting groups:

There is ample reason, then, for examining these great groups of acting men directly and accepting them as the fundamental facts of our investigation. They are just as real as they would be if they were territorially separated so that one man could never belong to two groups at the same time. ... Indeed the only reality of the ideas is their reflection of the group, only that and nothing more. The ideas can be stated in terms of the groups; the groups never in terms of the ideas.

Page 211, on groups, activity, and interests:

The term "group" will be used throughout this work in a technical sense. It means a certain portion of the men of a society, taken, however, not as a physical mass cut off from other masses of men, but as a mass activity, which does not preclude the men who participate in it from participating likewise in many other group activities. It is always so many men with their human quality. It is always so many men, acting, or tending toward action - that is, in various stages of action. ... It is now necessary to take another step in the analysis of the group. There is no group without its interest. An interest, as the term will be used in this work, is the equivalent of a group.

Page 227, on the source of group strength:

There is no essential difference between the leadership of a group by a group and the leadership of a group by a person or persons. The strength of the cause rests inevitably in the underlying group, and nowhere else. The group cannot be called into life by clamor. The clamor, instead, gets its significance only from the group. The leader gets his strength from the group. The group merely expresses itself through its leadership.

Page 347, on the deception of appearances:

Taking all the conditions, it would have been natural to expect that the tariff movement would have found a leader in Roosevelt, and have made a strong struggle through his aid, which, of course, is just what has not happened up to date. And the reason for this is exceedingly simple. It is not that Roosevelt "betrayed" the cause nor that he sacrificed it to the "trusts", but that under present conditions, despite all superficial appearances, there is not an intense enough and extensive enough set of interest groups back of the movement to make a good fight for thoroughgoing reform with reasonable prospects of success.

Page 348, on subsurface movements:

The essential point in an interpretation of government concerns the great pressures at work and the main lines of the outcome. It is relatively incidental whether a particular battle is fought bitterly through two or more presidencies, or whether it is adjusted peacefully in a single presidency, so long as we can show a similar outcome. This is true because the vast mass of the matter of government is not what appears on the surface in discussions, theories, congresses, or even in wars, but what is persistently present in the background. It is somewhat as it is when twenty heirs want to contest a will, but have only a single heir apparent in the proceedings, while the other nineteen hang back in the shadow. The story will concern the fight of the one; but the reality concerns the silent nineteen as well.

Page 418, on the inadequacy of policy to explain political parties:

Like all "theory", policy has its place in the process as bringing out group factors into clearer relation, and as holding together the parties, once they are formed, by catchwords and slogans. So far as it gives good expression to the groups on its particular plane, all is clear. But to attempt to judge the parties by their theories or formal policies is an eternal absurdity, not because the parties are weak or corrupt and desert their theories, but because the theories are essentially imperfect expressions of the parties.

The vicissitudes of states' rights as a doctrine are well known enough. Another passing illustration concerns the government regulation of commerce. If we may identify the commercial interests of a century ago with those of today for the purposes of illustration, we find that the very elements which then under Hamilton's leadership were most eager to extend the power of government over commerce are now the most bitterly opposed to any such extension. Then and now the arguments made great pretenses to logic and theoretical cocksureness, and then, as now, the theories were valuable in the outcome only as rallying the group forces on one side or the other for the contest.

Page 432, on writing legislation yourself:

Still more striking if the organization which at times can be found which produces what may almost be described as substitute legislatures. When there is some neglected interest to be represented, when the legislature as organized does not deal on its own initiative with such matters, when a point of support in party organization can be found - a point let us say of indifference, at which nevertheless the ear of some powerful boss can be obtained - a purely voluntary organization may be formed, may work out legislation, and may hand it over completed to the legislature for mere ratification.

Page 440, on leadership and personality cults:

A leader once placed will gather a following around him which will stick to him either on the discussion level or on the organization level within certain limits set by the adequacy of his representation of their interests in the past. That is, as a labor-saving device, the line of action in question will be tested by the indorsement of the trusted leader. The leader may carry his following into defeat in this way, but that very fact helps to define the limits of the sweep of groupings of this type.

Page 441, on the primacy of groups over forms of government:

The citizen of a monarchy who sees his kind ride by may feel himself in the presence of a great power, outside of him, entirely independent of him, above him. The man busy in one of the discussion activities of the time may look upon ideas as masterly realities self-existing. But neither ideas nor monarchs have any power or reality apart from their representation of reflection of the social life; and social life is always the activity of men in masses.

Page 442, on leadership and esprit de corps:

Not only are discussion groups and organization groups both technique for the underlying interests, but within them we find many forms of technique which shade into each other throughout both kinds of groups. In the older fighting, soldiers might sing as they went into battle, or an officer might go ahead waving the colors. The singing and the officer illustrate the technical work of the representative groups. They serve to crystallize interests, and to form them solidly for the struggle, by providing rallying points and arousing enthusiasm. For all that, it is the men organized behind the singing, the cheering, and the colors that do the fighting and get the results.