tecznotes

Michal Migurski's notebook, listening post, and soapbox. Subscribe to ![]() this blog.

Check out the rest of my site as well.

this blog.

Check out the rest of my site as well.

Feb 22, 2010 6:04am

user research friday

Nate Bolt of Bolt|Peters invited me to speak at User Research Friday last week. My obvious first reaction was "user research? We don't do any." Nate was interested in the perspective of a design firm that has no formal process for user testing or research, so I did my best to coalesce a bit of our most recent thoughts on astonishment and novelty for the packed house at their SOMA offices.

These are my talk notes and slides. Some of the things here actually came out of my mouth!

I'm here because Stamen Design doesn't do user research, and I hope I can explain why we've made that choice in our work and continue to stand by it.

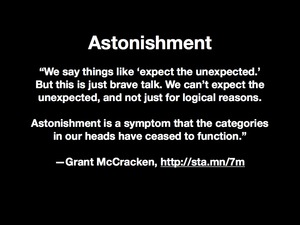

I'm going to show a few of our projects that I think benefitted from a lack of user research, but I'll start by talking a bit about astonishment. I've become interested recently in thinking about how people respond to novelty. Anthropologist Grant McCracken talks about astonishment as a "jamming" of your powers of action, an inability to function and respond to external events, a subversion your own sense of reality.

User research, to me, is an attempt to mitigate and control astonishment by determining what an audience believes or expects, and where possible delivering on that belief and expectation. User research promises stability and predictable outcomes, and I think that we're at a curve in the road where the idea of stability is just not all that interesting. I'm not arguing for chaos, but a kind of targeted novelty that probes out the edges of our expectations and helps us keep our beliefs and behaviors continually fresh.

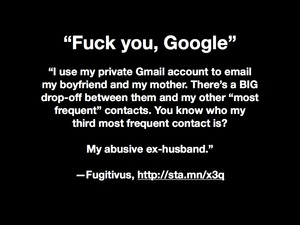

It's worth keeping in mind that targeted novelty can rapidly become chaos. Who here has heard of Google Buzz? Do you remember the announcement, accompanied by breathless claims of game-changing excitement? The rush to verb every noun and crown Google victor in the social wars of the late aughts? The launch of Buzz was a fascinating experiment in modifying expectations around email, the internet's most boring communication medium.

Unfortunately, it was also a total, unmitigated cluster fuck.

I think we have to assume that Google performed basic, ass-covering user research on this project, right? What do you think the odds are that in their user-testing labs they might have come across a user like Fugitivus, a blogger hiding from her abusive ex and using email to communicate with close family members? By involuntary launching Buzz at GMail's 175 million members, Google introduced the pressure of public performance into a private communication medium, outing human rights activists, confidential sources, secret friends and battered wives.

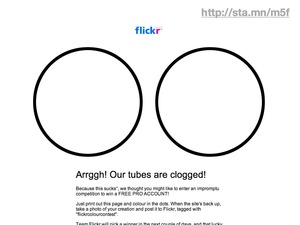

There's an alternative to the Buzz model of foisting novelty on people, and I think that Flickr is a classic example of a better way to operate on the web. Flickr is famous inside of Yahoo and out for having a basically cavalier attitude to commonly-accepted wisdom about testing, assurance, predicability, and all-around maturity. What that means is that sometimes, Flickr screws up. This is the Flickr coloring contest, hastily assembled during a multiple hour, unexpected engineering emergency from 2006. Flickr had and has a world-class community management approach that can respond to crisis with humor. The coloring contest kept anxious community members busy while terrifying technological feats were performed to unclog the tubes.

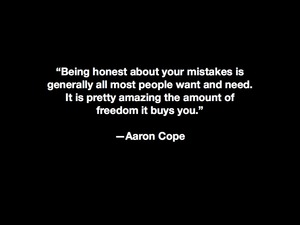

Aaron Cope, formerly of Flickr but presently with us at Stamen, believes that Flickr's ability to successfully respond with this kind of deft flexibility to a crisis is a result of a caring, trusting relationship between the site and its users. This relationship seems to extend to all areas of the site, from emergency management to regular day-to-day feature development that prizes speedy development, deployment, and public response over plans and assumptions. I believe that user research played very little role in the creation of experiences like Flickr, because the site is not something that could have been predicted or tested in lab: it's a whole-body novelty situation.

Sites like Flickr start small, and grow through organic additions to the user base. This short graph of Twitter's early history from Blaine Cook tells a similar story of humble beginnings, sudden floods of interest, rapid response to community desire, and ultimately the triumph of joy over pain through building and testing in public, with real people.

I'm going to show some of our work, but the point I'm making is: get the jetski out of the driveway and into the water.

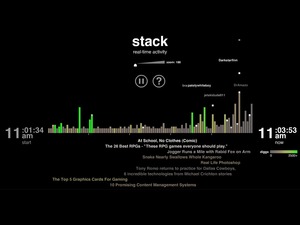

Labs was a dominant thread in Stamen's work from about 2006 through 2008. The project was blessed from the start: Kevin Rose contacted us personally, and was intimately involved in the sketching and development process of the first Labs pieces. Whatever you think about the Digg community - it's nerdy, and male, and everything else - Kevin was deeply in tune with the cultural tastes of his userbase. The video game metaphors and API development was all of a piece, and this was the kind of project that was going to see success just because the strong, visible leader of the community identified it as worthy of attention.

The site now looks like a completed artifact, but it's worth noting that at the time it was a wide open playing field. No one really knew what the "labs" terminology was going to mean, and no one was doing this kind of live community visualization on quite the same scale. Our own development testing put us in synch with the Digg community, and we were working with live data from day one. We'd pretty much have to wrap up our work by about 6:00pm PDT, because that's when the Digg community was in bed in Europe, at dinner on the East Coast, and commuting on the West Coast.

Many of the Labs pieces saw multiple public iterations that were a direct result of vocal, frequently bitchy feedback from the Digg community. All of it was valuable, and we did our research in the open, letting people see multiple iterations of the work. The hallmark of this project set was visibility and basic openness, which bought us a great deal of goodwill.

Who here is familiar with OpenStreetMap?

OSM is a freely-licensed world map created by volunteers in the style of Wikipedia. The project has always valued praxis over correctness. Founder Steve Coast claims that he developed the project after growing so frustrated with existing copyright regimes in the UK and refusing to bother with complicated specification documents showing how he ought to proceed.

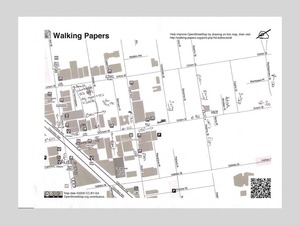

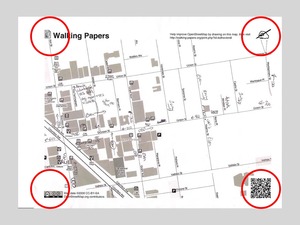

Walking Papers is an experimental, paper-based editing tool for OpenStreetMap. It's an alternative to cumbersome GPS technology, based on the use of the QR code, an application of basic computer vision for cell phones widely deployed in Japan but only just now becoming known in the US.

Here's a current ad on BART with Lawrence Hall of Science Geek Night event details stored in a QR code. I think this would have been unimaginable just a few years ago, but now you all have magic touch computers with cameras in your pockets, so here we are.

When you pair the QR code with OpenStreetMap, you get a printable piece of paper that can encode basic information about its geography in a machine readable form.

Users of Walking Papers mark up these maps with information they'd like to add to OpenStreetMap, scan those maps in, and then trace their additions in existing OSM tools normally designed for tracing GPS trails or aerial imagery.

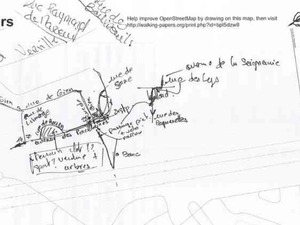

The first thing that surprised me when launching the project was that US users were a surprising minority of the base. Here are a user's notes from Mennecy, France.

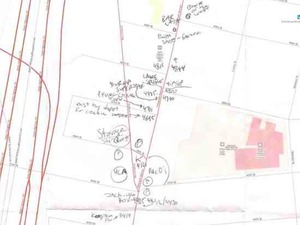

This is me making notes about businesses along Telegraph Avenue, in Oakland's Temescal District. Lanesplitter Pizza is in the center.

This is a rain or sweat smudged map of individual address points from the UK.

We didn't know it at the time, but a lot of geographic data collection happens using simple paper tools that talk to one another.

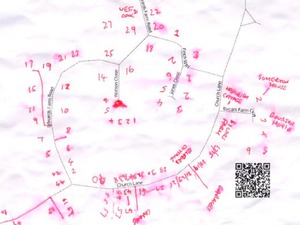

The second thing that surprised me was that I had unwittingly stumbled into a sort of holy grail of the disaster response community. This photo is of an adaptation I made to Walking Papers at an event in Camp Roberts, CA, which combined up-to-date satellite imagery of Afghanistan with photography from test flights of unmanned aerial vehicles. All the conversations I've since had about Walking Papers have focused less on the ease of carrying pieces of paper around San Francisco, and more on the need to use paper in remote environments.

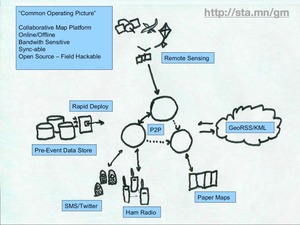

It turns out that members of the OSM foundation had already been considering the universe of possibilities around data input and output. In this napkin sketch from Mikel Maron, we see paper in the corner with a double-headed arrow that he says was a joke at the time. The rest of the picture shows possible connections to other parts of the web, other kinds of hardware. None of this was within our view when we first started thinking about the paper issue in isolation.

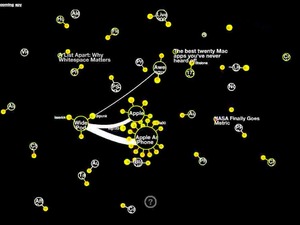

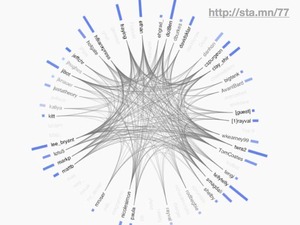

The O'Reilly Emerging Technology conference had a long-time IRC-based backchannel where participants could chat about sessions and speakers as they were happening. It relied on a 20 year old technology comfortable and natural for Unix hackers but not so much for journalists, designers, and other normals. Still, we used the opportunity to eavesdrop on this live communication channel in an automated fashion to create these live, self-updating diagrams of who was talking to whom while the event progressed. I think we've always been interested in ways of tapping into ongoing conversation streams and showing them back to their participants, but in the past this has meant cajoling people to make a special effort to come to a shared medium like IRC. The #etech channel was live for the duration of the event, and effectively dead afterward.

Fast forward to now, and suddenly all these dreams we had about visualizing ongoing conversations can be made real because of the explosive growth of Twitter. What makes Twitter interesting is that it's a performative medium, a place where you know you're being listened to and write as though you are in public. It's broadcast, and explicitly so. It's interesting because very little of the Twitter we know now could have been predicted or tested for beforehand. It could only be used in the wild and reacted to. Like Google Buzz earlier, you simply have to try it *with everyone else* to know whether it makes sense or not.

Metafilter's Matt Haughey used it last year to spread the news about his diagnosis of a brain tumor, and thought a bit about use of the service in emergency situations. What can you predict about a service when what you want it to become a utility?

It's so incredibly interesting, we've been doing a bunch of work with Twitter since last year.

This is our live tracking application for the 2009 MTV Video Music Awards. On these screens, you can see each artist or performer represented as a jiggling chit that shrinks and grows based on the live conversation volume about that person. Here we can see a bit of conversation about Pink and Shakira.

You might remember the moment when Kanye West interrupted Taylor Swift's acceptance speech. Here it is replayed as a bubble graph, with the two stars on the screen at the same time, followed by instantaneous crowd disapproval of Kanye West.

So, this kind of crowd call and response is something that we think is going to get pretty important over the next few years. It's going to be especially interesting because it's going to become normal and expected over that time.

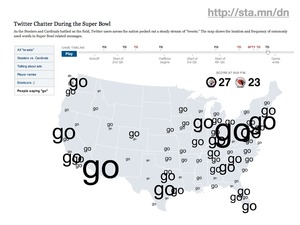

Every live event will come with a live analysis of what the audience is doing, like a country-scale version of those America's Funniest Home Videos audience clicker boxes. The amazing graphics department at the New York Times thought it was interesting to map live Twitter traffic during last year's Superbowl, as entertainment and information.

Right now, we have an ongoing project with NBC Olympics exploring these same themes in the form of a dynamic, self-updating tree map.

At this point in my talk prep, I stopped writing everything down and ad-libbed it all. In and amongst all these bits of NBC Olympics stuff, I called out this amazing NPR blog post about the "weird poetry" of the twitter tracker.

Summing Up

The negative way of phrasing my argument is that it's hard to test everything, and doubly hard to test new things. Some stuff you just have to push out into the world and see what happens.

The positive way of phrasing my argument is that for the astonishing and the novel, you're better off pushing your ideas into the real world early, and testing with the reactions of real people who aren't self-consciously test subjects. Start small, listen carefully to your users, and grow in the direction where they want to take you. Give yourself room to fail, and understand that the trust of your fellow travelers is an important part of the equation.

The doubly-positive way of phrasing my argument is Just Effing Do It.

Comments (3)

Really inspiring and funny. Appreciate you making the slides available too. I don't usually sit thru 46 minute video, but you had me. thank you!

Posted by PJ cich on Monday, February 22 2010 7:40pm UTC

Thanks PJ!

Posted by Michal Migurski on Monday, February 22 2010 9:24pm UTC

This fits right in with some stories in Malcolm Gladwell's "What the dog saw" about minor geniuses, such as the guy behind Ronco: doing no user research at all and coming up with gadgets which sold really well.

Posted by Monty on Monday, February 22 2010 10:18pm UTC

Sorry, no new comments on old posts.