tecznotes

Michal Migurski's notebook, listening post, and soapbox. Subscribe to ![]() this blog.

Check out the rest of my site as well.

this blog.

Check out the rest of my site as well.

Jul 28, 2016 11:07pm

openstreetmap: robots, crisis, and craft mappers

The OpenStreetMap community is at a crossroads, with some important choices on where it might choose to head next. I spent last weekend in Seattle at the annual U.S. State Of The Map conference, and observed a few forces acting on OSM’s center of gravity.

I see three different movements within OpenStreetMap: mapping by robots, intensive crisis mapping in remote areas, and local craft mapping where technologists live. The first two represent an exciting future for OSM, while the third could doom it to irrelevance.

The OpenStreetMap Foundation should make two changes that will help crisis responders and robot mappers guide OSM into the future: improve diversity and inclusion efforts, and clarify the intent of OSM’s license, the ODbL.

Robot Mappers

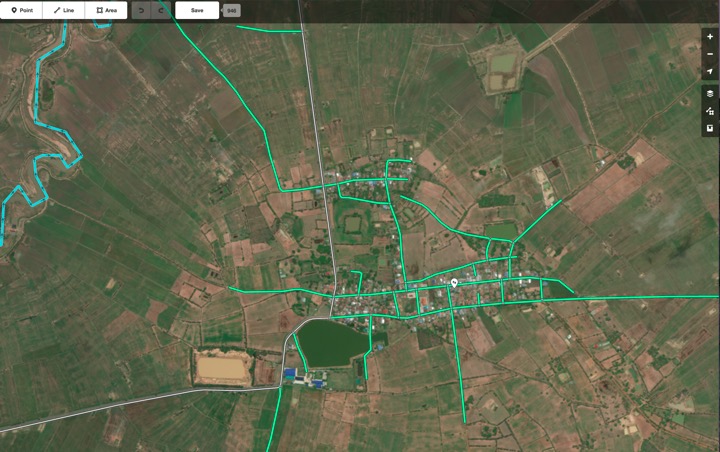

Engineers from Facebook showed up to talk about how machine-learning and artificial intelligence (“robot”) techniques might help them produce better maps. Facebook has been collaborating for the past year with another SOTMUS attendee, DigitalGlobe, to consume and analyze high-resolution satellite imagery searching for settled areas as part of its effort to expand internet connectivity.

However, there are still parts of the world in which the map quality varies. Frequent road development and changes can also make mapping challenging, even for developed countries. … In partnership with DigitalGlobe, we are currently researching how to solve this problem by using a high resolution satellite imagery (up to 30cm per pixel). … For small geographical areas, this technique has allowed our team to contribute additional secondary and residential roads to OSM, offering a noticeable improvement in the level of details of the map.

OSM has long had a difficult relationship with so-called “armchair mapping,” and Facebook’s efforts here are a quantum leap in seeing from a distance. This form of mapping typically requires the use of third party data. For sources such as non-public-domain satellite imagery, robot mappers must be sure that licenses are compatible with derived data and OSM’s own ODbL license. Copyright concerns can make or break any such effort. Fortunately, OSM has a sufficiently high profile that contributors rarely attempt to undermine the ODbL directly. Instead the choose to cooperate with its terms, to the extent they understand the license.

Crisis Mappers

Meanwhile, representatives of numerous crisis mapping organizations showed to talk about the use of OSM for mapping vulnerable, typically remote populations. Dale Kunce of the Red Cross Missing Maps project gave the second day keynote, while Lindsey Jacks gave an update on her work with Field Papers (Stamen’s ongoing product I originally called Walking Papers) and numerous members of organizations like Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT), Digital Democracy, and others attending workshops on collecting data.

Disaster response and crisis mapping organizations take a more direct, on-the-ground approach to map features that can’t be seen remotely or require local knowledge to interpret. While these efforts have often used remote data, as in the satellite-aided Haiti earthquake response in 2010, that data has always been paired with ground efforts in the area concerned.

When major disaster strikes anywhere in the world, HOT rallies a huge network of volunteers to create, online, the maps that enable responders to reach those in need. … HOT supports community mapping projects around the world and assists people to create their own maps for socio-economic development and disaster preparedness.

The populations most in need of crisis-response mapping efforts are typically furthest from OSM’s W.E.I.R.D. founding core. Such efforts will succeed or fail based on their participation. OSM should do a better job of welcoming them.

Craft Mappers

Historically, OpenStreetMap activity took place in and around the home areas of OSM project members, as a kind of weekend craft gathering winding up in a local pub. OSM originated from a mapping party model. Western European countries like England, Germany, and France achieved high coverage density early in the project’s history due to active local mappers carrying GPS units, riding bikes to collect data, and getting together at a pub afterward. Mapping pubs and similar amenities was a cultural touchstone for the project’s founding participants. The project has always featured better-quality data in areas where these craft mappers lived, for example near universities with computer science or information technology programs.

Many historic OSM tendencies, such as aversion to large-scale imports and a distinctly individualist technical worldview, are the result of this origin. They mirror the histories of other open source and open data projects, which often start as itch-scratching projects by enthusiastic nerds. Former OSM Foundation board member Henk Hoff’s 2009 “My Map” keynote is a great example of OSM’s early focus on areas local to individual mappers. The founding work of this branch of the community treats the project as a kind of large-scale hobby, like craft brewing or model railroading.

At its current stage of development, OSM’s public communications channels seem to be divided amongst these communities. I heard much frustration from crisis mappers about the craft-style focus of the international State Of The Map conference in Brussels later this year, while the hostility of the public OSM-Talk mailing list to newcomers of any kind has been a running joke for a decade. The robot mappers show up for conferences but engage in a limited way dictated by the demands of their jobs. Craft mapping remains the heart of the project, potentially due to a passive Foundation board who’ve let outdated behaviors go unexamined.

It’s a big downer to see a fascinating community mutely sitting out important discussions and decisions about the community’s future. Left to the craft wing, OSM will slide into weekend irrelevance within 5-10 years.

Two Modest Proposals

Two linked efforts would help address the needs of the crisis response and robot mapping communities.

First, U.S. technical gatherings like PyCon have been invigorated over the past years by codes of conduct and other mechanisms intended to welcome new participants from under-represented communities. State Of The Map US has done a great job at this, but the international conference and foundation seem to be engaging only in passive efforts, if any. A prominent code of conduct for in-person and online events would bring OSM in-line with advances in other technology forums, who have chosen to value the contributions of diverse participants. With the appearance of crisis and disaster mapping on the OSM landscape over the past five years, we need to appeal to people of color disproportionately affected by crises and disasters, so they understand they are welcome within OSM’s core. Ignoring this or settling for “#FFFFFF Diversity” is a copout.

Ashe Dryden says this about CoC’s at events with longtime friends running the show:

We focus specifically on what isn't allowed and what violating those rules would mean so there is no gray area, no guessing, no pushing boundaries to see what will happen. "Be nice" or "Be an adult" doesn't inform well enough about what is expected if one attendee's idea of niceness or professionalism are vastly different than another's. On top of that, "be excellent to each other" has a poor track record. You may have been running an event for a long time and many of the attendees feel they are "like family", but it actually makes the idea of an incident happening at the event even scarier.

Second, the license needs to be publicly and visibly explained and defended for the benefit of large-scale and robot participants. ODbL FUD (“fear, uncertainty, and doubt”) is a grand tradition since the community switched licenses from CC-BY-SA to ODbL in 2012. I support the share-alike and attribution goals of the license. But passive communication about its intent and use has left the door wide open for unhelpful criticisms. OSM Foundation publishes community guidelines on a separate wiki rather than a proper website. It’s not enough: the license needs to be promoted, defended, and consistently reaffirmed. Putting it under active discussion may even make it possible to adapt to new needs via a mechanism like Steve Coast’s license ascent, where “work starts out under a restrictive and painful license and over time makes its way into the public domain.”

I’ve struggled to write this post without overusing the word “actively,” but it’s the heart of what I’m suggesting. OSMF Board has been at best a background observer of project progress, while OSM itself has slowly moved along Simon Wardley’s “evolution axis” from a curiosity to a utility:

A utility like today’s OSM requires a different form of leadership than the uncharted and transitional OSM’s of 2005-2010. There are substantial businesses and international efforts awkwardly balanced on a project still being run like a community garden, without visible strategy or leadership.

Thanks to Nelson, Mike, Kate, and Randy for their input on earlier drafts of this post. I am an employee of Mapzen, a Samsung-owned company that features OSM and other open data in our maps, search, mobility, and data products.